Broiler operations naturally want to provide the best disease protection for the least cost, but deciding which vaccines to use and when can be a daunting task.

First, there are so many variables to consider — not just disease pressure and the emergence of new variants but also geographic location, proximity to other farms, temperature, litter moisture, housing type, ventilation, lighting, bird density, target weight and labor.

Then there’s the overwhelming arsenal of vaccines. Producers have a deep war chest of modified-live, inactivated, autogenous and recombinant vaccines that can be administered in a variety of ways, at different times — often in combination with other immunizations.

Every flock and farm is different, and there’s no such thing as a blanket program. So how should broiler farms go about planning cost-effective vaccination programs? And how does one vaccine decision affect a poultry company’s options for managing other diseases?

Poultry Health Today asked two experts with extensive experience evaluating vaccination programs on hundreds of farms — Kalen Cookson, DVM, MAM, and Lloyd Keck, DVM, ACPV — for help in navigating the path to sensible, strategic and cost-effective disease protection.

Square one

What to use for Marek’s disease (MD) is usually the first step toward planning a broiler-vaccination program. Even though the incidence of tumors is generally low in US broilers, the MD virus is ubiquitous and always a potential cause of immune suppression. “That’s why all broiler operations continue to immunize their flocks against this highly contagious disease,” Cookson says.

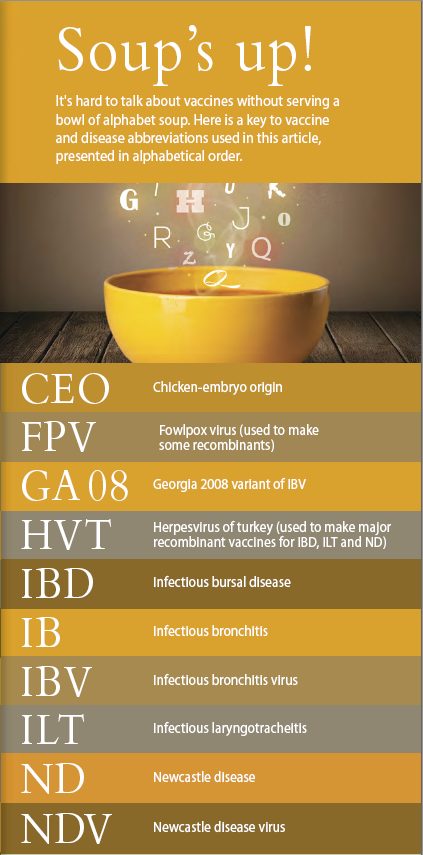

While traditional live vaccines for MD are available, many US broiler operations obtain MD protection from a herpesvirus of turkey (HVT) recombinant vector vaccine administered in ovo. HVT helps protect against MD and serves as a vector to help provide protection against one of three other costly diseases — infectious bursal disease (IBD), infectious laryngotracheitis (ILT) and/or Newcastle disease (ND).

While traditional live vaccines for MD are available, many US broiler operations obtain MD protection from a herpesvirus of turkey (HVT) recombinant vector vaccine administered in ovo. HVT helps protect against MD and serves as a vector to help provide protection against one of three other costly diseases — infectious bursal disease (IBD), infectious laryngotracheitis (ILT) and/or Newcastle disease (ND).

Though more expensive than traditional vaccines, the recombinant vector vaccines are popular with broiler producers because they’re easy to administer and safe, and do not impede flock performance.

However, because only one HVT vaccine can be used — whether recombinant or not — producers have to make a calculated choice, Cookson says. They can use a single-insert product for the disease that’s most crucial for them — HVT plus IBD, for example — and then use conventional vaccines to tackle the other disease challenges; or they can use one of the double-insert HVT vaccines available, such as HVT plus IBD and ND.

The approach one takes in selecting recombinant and/or conventional vaccines is both philosophical and situational. That’s why we see a variety of programs and we’ll probably never see a “one size fits all” strategy.

Choosing your weapon

So, if broiler farms get only one shot with an HVT-based recombinant, which disease or diseases should they target?

It really comes down to disease pressure, time of year and other vaccination options. Keck recommends using lab testing and physical evidence of disease damage as a starting point. “You want to find the recombinant that’ll deliver the most value in each particular situation,” he says. “Then use traditional vaccines to manage the other major diseases.”

Here’s an overview of four different vaccine scenarios for broilers, with and without recombinants:

PROGRAM A:

USING A RECOMBINANT FOR IBD

When to consider it

Recombinant IBD vaccines are usually the first choice when ILT, ND and infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) pressure is low and growers are faced with a high — or early — IBD challenge.

Winter and spring are peak challenge times for IBD due to lower temperatures and reduced ventilation, which increase the concentration of the virus and field challenge over time.

The recombinant IBD vaccine has been demonstrated to be highly effective on many farms.

However, growers must remember that continuous use of a recombinant IBD vaccine only buffers the challenge from the field virus. The viral load and production losses will usually decrease, but the virus continues to replicate, Cookson says. “That allows reinfection in the next cycle of birds and the possible selection of more ‘fit’ subpopulations over time,” he adds.

The level and type of maternal antibodies broiler chicks inherit play a key role in any effective IBD-control program. “That’s because passive immunity is the most efficient way to prevent infections in the first 10 to 14 days in the broiler,” Cookson says.

“You want your vaccines to match the field challenge as closely as possible. Field surveys over the past few years show that over 80% of IBDVs infecting broilers are antigenically distinct from Del-E. The lion’s share of these ‘new types’ are AL2 viruses,1 but there are others as well. These viruses put more pressure on the breeder program by infecting broiler flocks sooner.”

Even recombinant vaccines that offer early protection against classical IBD may not achieve the same level or early protection against AL2 or other variants, he adds. “Fortunately, bursal-health surveys are an effective way to monitor field challenge vis-à-vis our vaccination program.”

Options for managing ILT

Customers using an HVT-IBD vaccine that suddenly need to vaccinate for ILT are faced with a few options. They can stay on HVT-IBD and add either fowl pox (FP)-ILT or live chicken-embryo origin (CEO)-ILT vaccine, they can switch to HVT-ILT and a live IBD vaccine, or they can switch to a newer HVT containing both IBD and ILT genes. The decision tree for ILT vaccination is the most complicated of all because ILT control often involves coordination between companies and, frankly, no vaccine type offers a perfect solution, Cookson says.

The gold standard for ILT control, particularly in large birds, is the modified-live CEO vaccine.

A CEO vaccine can produce a “sterilizing immunity” against the ILT virus and helps break the challenge cycle, Cookson explains. At the same time, however, the CEO vaccine has the potential to spread the disease to unvaccinated birds. Strict biosecurity helps reduce the spread of ILT between vaccinated and unvaccinated barns.

Farms planning to begin a CEO vaccination program should increase biosecurity measures, share plans with neighboring farms and encourage collaboration on vaccination programs.

Options for managing ND

Without a recombinant ND vaccine in the mix, producers must select more traditional ND vaccines, based on disease pressure and history. Available vaccines vary from the lower-reactive C2 and VG strains through the less-attenuated B1 strains.

During winter months, many operations choose to use a C2 or VG vaccine — one that limits reactivity and helps growers avoid putting additional stress on the birds, Cookson says. However, using these vaccines year-round allows field-virus levels to build — eventually making them less effective, particularly against a late NDV challenge.

Cookson recommends “moving up the reactivity/efficacy scale” during summer with a vaccine such as Poulvac Aero®. “That ‘re-set’ approach will help to decrease circulating virus levels and help prevent late-season challenge surprises,” he explains.

PROGRAM B:

USING A RECOMBINANT FOR ILT

When to consider it

Once viewed as a cold-season virus, ILT has become a year-round threat in many broiler-production strongholds of the US. Cold, wet weather and reduced ventilation often trigger ILT outbreaks.

Producers frequently choose to use a recombinant ILT vaccine in situations of low challenge or if the challenge is not present but there is a risk of exposure, particularly in medium-sized birds.

A recombinant vaccine can also be used to jump-start ILT protection and serve as a reaction buffer when a modified-live field vaccine is needed at 14 days.

Keck says that in cases of very high risk or outbreak situations, a recombinant ILT vaccine administered in ovo, followed by a CEO vaccine in the field, may be needed to help reduce mortality levels and ensure ILT immunity. “If a grower is seeing very high mortality rates, the cost of two vaccinations may save money in the long run,” he explains.

When transitioning off a modified-live vaccine program, producers can opt to use a recombinant vaccine in ovo to help buffer against what has hopefully become a diminishing field challenge. It can also be insurance against any residual vaccine persistence.

According to Keck, birds raised to less than 4 pounds (or 5 weeks of age) seldom exhibit mortality from ILT. So, unless growers are facing an outbreak, it may not pay to vaccinate small birds. If an ILT recombinant is needed in a small bird, the FPV recombinant vaccine can be used since it costs less than the HVT vector vaccines.

Bottom line: Each farm needs to look at its history, the surrounding production area, and the age and weight of birds when selecting its primary and secondary options for ILT vaccination.

Options for managing IBD

Using a recombinant ILT vaccine presents more options for managing IBD. Among conventional modified-live vaccines, Cookson recommends either using a mild IBD vaccine with MD, or an intermediate vaccine that can be administered at 8 to 10 days or with a ND/IBV field boost at 14 to 18 days.

Administering an immune-complex vaccine such as Bursaplex® along with a MD vaccine in ovo is another option. This type of vaccine helps provide strong IBD protection as maternal antibodies decline, he says, thus delaying and reducing the period of infection while allowing for quicker recovery of the bursa of Fabricius — a specialized organ necessary for B-cell development in birds.

Another way to help reduce IBDV levels is to continue vaccinating throughout the summer. Summertime vaccination combined with better ventilation rates reduces IBD pressure going into the following winter.

“Of course, with any of these options, the better the breeder program, the better the broiler program will perform,” Cookson says.

“As we already mentioned, AL2 is the most prevalent field challenge we see today, so the better you can control AL2 from the breeder side, the more successful your broiler vaccination options will be.”

Options for managing ND

(See ND recommendations under Program A.)

PROGRAM C:

USING A RECOMBINANT FOR ND

ND peaks in the winter and spring months when cold, wet weather and reduced ventilation rates help respiratory viruses build up. A recombinant, HVT-based ND vaccine helps offer growers “peace of mind” protection, Cookson says, while allowing them to focus live respiratory vaccination on IBV, which also spikes in winter. (See IBV recommendations in the next section.)

While the recombinant ND vaccine is more expensive, it offers little reactivity with moderate- to high-level disease control. Fortunately, circulating ND viruses across most of the US are not extremely pathogenic and tend to infect at later ages, allowing recombinant ND vaccines the opportunity to be effective in most situations.

However, there are some regions that do have a more aggressive ND challenge. In those cases, the selection of live ND or HVT-ND should become more important. Again, the ND vaccine decision must be based on flock history and challenge levels.

Options for managing IBD

(See IBD recommendations under Program B.)

Options for managing ILT

(See ILT recommendations under Program A.)

PROGRAM D

USING NO RECOMBINANTS

When to consider it

Recombinant vaccines are still a fairly recent addition to the poultry-vaccine arsenal. Cookson estimates that at least one-third of all broiler operations still do not include recombinants in their vaccination programs today.

“It really comes down to perceived need versus cost of the recombinant,” he explains.

Many producers still grow chickens without recombinants, based on their flock history, good disease coverage with their current vaccination plan and to avoid the higher cost associated with recombinants.

Options for managing Marek’s disease

Of course, MD can be safely and effectively controlled by using non-recombinant vaccines. The key is to adjust the MD program to help provide adequate protection against tumors and performance losses. It is important to remember that tumor formation is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to MD in broilers. Immune suppression, while often nebulous and difficult to pin on any one etiology, is a very real and costly manifestation of MD. For many broiler operations, this has meant developing different vaccination programs for summer versus winter.

Options for managing IBD, ILT and ND

(See recommendations for each in Programs A and B.)

Complex decisions require expert advice

Developing a vaccination program targeting optimal performance and return requires more planning and expertise than local “experts” at the farm store can offer. Relying on professional advice helps producers avoid the shotgun approach — shooting at everything with the hope it hits something — which often results in increased costs and reduced disease coverage.

Producers and veterinarians must rely on thorough testing to pinpoint effective vaccine choices and timing. A combination of diagnostics ranging from visual inspection to PCR and histopathology are needed to correctly identify the diseases and variants present in their flocks.

For instance, the chicken embryo origin (CEO) vaccine is vital in controlling outbreaks of ILT in medium and large birds but can result in lost production and income potential when used in small birds due to fever and inappetence associated with vaccination.

The vaccination spectrum ranges from in ovo vaccines to day-of-age vaccines at the hatchery to field vaccines. The field vaccines, in particular, can be stressful for birds and increase labor costs. The monetary cost of the vaccine along with often subtle production costs associated with vaccination are just two of the many factors in the decision process associated with an effective vaccination program.

All trademarks are the property of Zoetis Services LLC or a related company or a licensor unless otherwise noted.

1. Cookson K, et al. A survey of wild type IBDV isolated from broiler flocks in the United States since 2014. 2020 International Poultry Scientific Forum, Atlanta, Georgia.

BIO-00290