Introduction

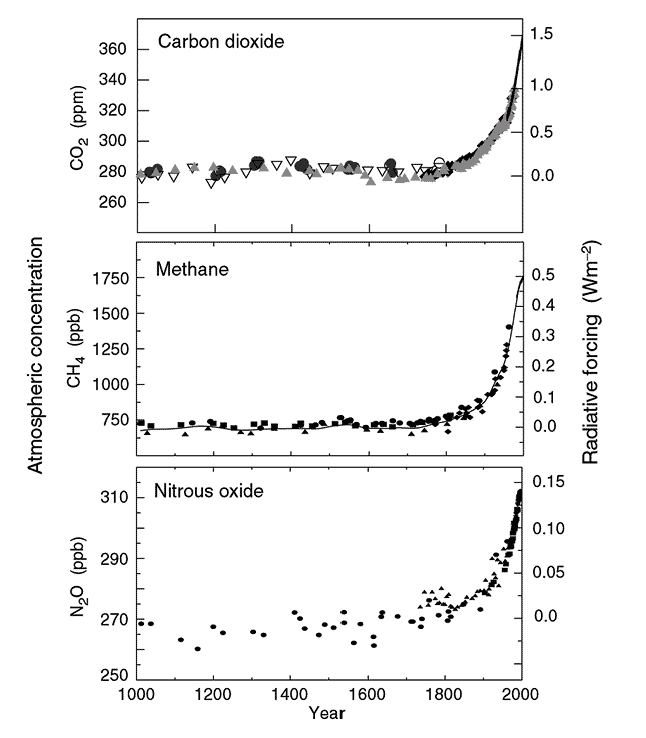

Figure 1. Changes in atmospheric concentrations of GHGs (IPCC, 2006).

Figure 1. Changes in atmospheric concentrations of GHGs (IPCC, 2006).The on-going debate on global warming has left some people convinced that human activity is seriously impacting climate change. Others are skeptical and dismissive. Whether you believe global warming is real or imagined, we know that the atmospheric concentrations of certain gases are increasing rapidly to levels that we have not seen before (Figure 1). While the impacts of these increased concentrations on climate is less certain, it is believed that these gases will trap heat in the atmosphere and could lead to global warming. Therefore, agriculture and other sectors are under increasing public pressure to reduce emissions of these gases. Even still, by knowing the carbon footprint (energy use) of your operation, you can not only reduce your energy usage, but also improve your bottom line.

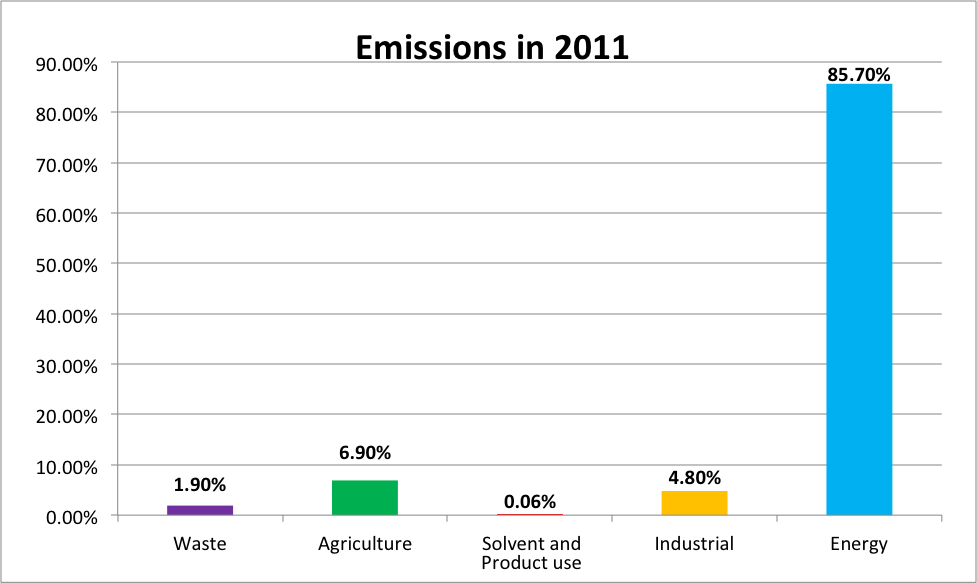

The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2008 (H.R.2764) included a provision that directed the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to require mandatory reporting of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from all sources in all sectors in the U.S. economy. Even though the EPA (2013) estimated that only 6.9 percent of U.S. GHG emissions come from agriculture, this law has raised the collective attention of the agricultural sector (Figure 2). Of this 6.9 percent, beef cattle accounted for about 37 percent, dairy cattle accounted for 11.5 percent, swine accounted for 4.4 percent, and poultry accounted for 0.6 percent, according to the USAF Greenhouse Gas Inventory, 1990-2011. While the figures for poultry production appear to be low, understanding how these GHG are generated and what we in the poultry industry can do to further reduce our impact remains important.

Figure 2. Relative contribution to greenhouse gas emission by major emitters in the United States.

Figure 2. Relative contribution to greenhouse gas emission by major emitters in the United States.What Are Greenhouse Gasses?

contribute to GHG emissions. Greenhouse gasses are defined by their radiative forces (defined as the change in net irradiance at atmospheric boundaries between different layers of the atmosphere), which change the earth’s atmospheric energy balance. These gases can prevent heat from radiating or reflecting away from the Earth, and thus, may result in atmospheric warming. A 1996 report published by the International Panel on Climate Change showed that GHG levels have increased since the Industrial Revolution (Figure 1). GHGs of particular concern (Figure 3) include carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrous oxide, methane, hydrofluorocarbons, and sulfur hexafluoride. Billions of tons of carbon in the form of CO2 are absorbed by oceans and biomass and are emitted into the atmosphere naturally. The concentrations of global atmospheric CO2 have risen since by about 36 percent the Industrial Revolution. This increase is primarily due to the combustion of fossil fuels. In 2008 in the U.S., fossil fuel combustion accounted for 94.1 percent of CO2 emissions (U.S. EPA, 2010).

Figure 3. Distribution of greenhouse gas emissions. High global warming potential (GWP) gasses include: hydroflorocarbons, sulfur-hexafluoride, and per-fluorocarbons (U.S. EPA, 2010).

Figure 3. Distribution of greenhouse gas emissions. High global warming potential (GWP) gasses include: hydroflorocarbons, sulfur-hexafluoride, and per-fluorocarbons (U.S. EPA, 2010).Changes in land use and forestry practices can also emit CO2 or act as a sink for CO2. Within the agricultural sector, nitrous oxide and methane are of primary concern, as most of the others are not typically associated with agricultural sources. Nitrous oxide is mainly emitted as a by-product of nitrification (aerobic transformation of ammonium to nitrate) and denitrification (anaerobic transformation of nitrate to nitrogen gas), which commonly occurs when fertilizers are used. Methane is emitted when organic carbon compounds break down under anaerobic conditions. These anaerobic conditions can occur in the soil, in stored manure, in an animal’s gut during enteric fermentation (mainly in ruminants), or during incomplete combustion of burning organic matter.

Several other gasses that are of interest because they may be converted into GHG, including nitrogen oxide, ammonia, non-methane volatile organic compounds, and carbon monoxide. In another report the IPCC stated that these precursor gasses are considered indirect emissions and are usually associated with leaching or run-off of nitrogen compounds applied to the soil (IPCC, 2006). The EPA estimated that in 2008 about 15 percent of total GHG emissions were methane and nitrous oxide, of which 36 percent and 77 percent, respectively, were directly attributable to agriculture (U.S. EPA, 2010).

What Does “Carbon Footprint” Mean?

Over the past several years, the term “carbon footprint” has often been used in conversations as public debate heightens on responsibility and mitigation practices that can be used to stem the threat of global climate change. In general, the term is a reference to the sum of gaseous emissions that are relevant to climate change associated with any given human activity. An ISO Research Report in 2007 defined it as the measure of the exclusive total amount of CO2 emissions that are directly or indirectly caused by an activity or is accumulated over the life stages of a product. In other words, your carbon footprint is a measure of the amount of GHG that are being emitted to the atmosphere because of your activity or product.

Contrary to what the word implies, a carbon footprint involves not only CO2 emissions but also includes other greenhouse gas emissions, which are expressed in CO2 equivalents (CO2e). A CO2e is the concentration of CO2 that would give the same levels of radiative properties as a given amount of CO2. The global warming potential (GWP) is a measure of how much a given mass of GHG is estimated to contribute to global warming. This is calculated over a specified time period and must be stated whenever a GWP is stated. For example, GWP over 100 years for nitrous oxide is 298. This means that the emission of 1 million tons of nitrous oxide is equivalent to 298 million tons of CO2 over 100 years. The GWP over 100 years for methane is 25. Therefore, a gas like methane has 25 times as much global warming potential as CO2 and nitrous oxide has 298 times as much GWP as CO2.

Carbon Dioxide, Nitrous Oxide, and Methane: Their Relationship with the Poultry Industry

Much of the CO2e that is generated from the poultry industry is primarily from the utilization of fossil fuels. This may be from purchased electricity, propane use in stationary combustion units (such as furnaces or incinerators), and diesel use in mobile combustion units such as trucks, tractors, and generators that are used on the farm. In the animal industry, the consumption of plants (feed) by animals eventually results in the division of the carbon into animal biomass (meat and eggs), CO2 respired by animals, and fecal deposition of carbon in unutilized coproducts (manure).

Aside from the emissions from fossil fuel used on poultry farms, these nitrous oxide and methane gases are also emitted from manure during handling and storage. Nitrous oxide and methane emissions are dependent on management decisions about manure disposal and storage as these gases are formed in decomposing manures as a by-product of nitrification/ denitrification and methanogenesis, respectively. Stored manure will only be emitting nitrous oxide if nitrification occurs, which is likely to take place provided there is adequate supply of oxygen. Also, indirect GHG emissions of ammonia and other nitrogen compounds occur from manure management systems and soils.

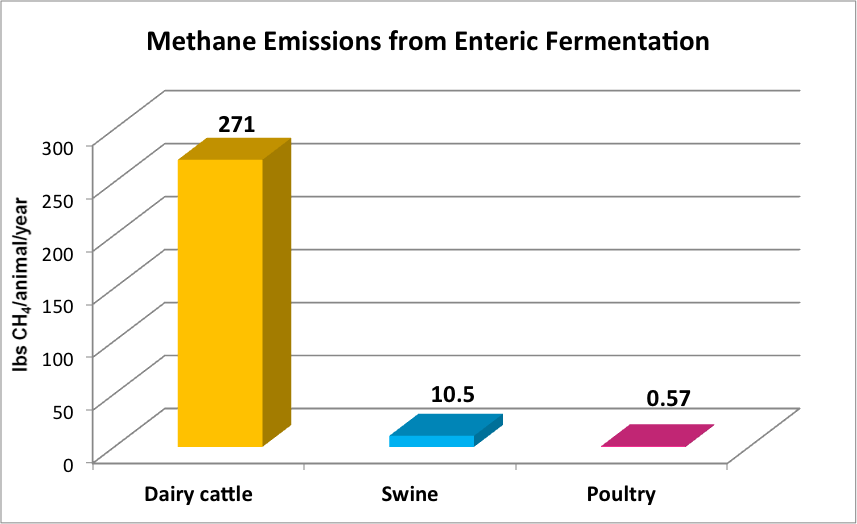

Figure 4. Methane emissions from enteric fermentation in pounds (lbs.) based on animal type. The figure represents emissions per animal per year.

Figure 4. Methane emissions from enteric fermentation in pounds (lbs.) based on animal type. The figure represents emissions per animal per year.In animal agriculture, the greatest contribution to methane emissions is enteric fermentation (23 percent) and manure management (9 percent). Enteric fermentation is the most important source of methane in dairy production, while most of the methane from poultry and swine production originates from manure. When comparing the distribution of methane emissions from enteric fermentation among animal types (Figure 4), poultry had the lowest amount with 0.57 pounds of methane per animal per year when compared to dairy cattle, which produces 185 to 271 pounds of methane per animal per year, and swine, which produce 10.5 pounds of methane per animal per year (Monteny, Groenestein, & Hilhorst, 2001).

Of course one must consider the size (weight) of the livestock and the amount of each type of livestock grown each year. Larger animals will produce more methane than smaller animals, and the amount of methane emitted is increased with increasing number of animals grown. The type of digestive system will also determine the amount of methane produced. Cattle are polygastric animals with a four-compartment stomach. Their digestive tract is designed for microbial fermentation of fibrous material. One of the by-products of microbial fermentation is methane. Poultry and swine are monogastric animals with a simple stomach where little microbial fermentation takes place; therefore, they produce less enteric methane.

The amount of manure produced depends on the number of animals reared plus the rate of waste production. Anaerobic decomposition depends on the type of manure storage. The majority of poultry production systems handle manure as a solid, and the manure thereby tends to decompose under aerobic conditions generating less methane than would be generated under anaerobic conditions.

The main cause of agricultural nitrous oxide emissions is the application of nitrogen fertilizers and animal manures. Application of nitrogenous fertilizers and cropping practices are estimated to cause 78 percent of total nitrous oxide emissions (Johnson, Fransluebbers, Weyers, & Reicosky, 2007). The EPA (2011) reported that manure from all livestock is a contributor to nitrous oxide emissions, with poultry accounting for 8.8 percent of manure nitrogen.

Nitrous oxide can be produced directly or indirectly through nitrification or denitrification of the nitrogen in the manure. Sixty-five percent of all nitrous oxide emissions from stored manure result from soil microbial nitrification and denitrification. The loss of nitrogen from manure as gaseous emissions depends on how the manure is stored and how it is applied to the land. Indirect emissions result from volatile nitrogen losses primarily in the form of ammonia and nitrogen oxide compounds.

The amount of excreted organic nitrogen mineralized to ammonia during manure collection and storage depends on time and temperature. In the case of poultry, uric acid is quickly mineralized to ammonia nitrogen, which due to its volatility, is easily diffused into the surrounding air. On the other hand, injecting or incorporating manure into the top layer of soil reduces ammonia emissions, but can increase emissions of other nitrogen compounds.

How Can the Industry Address Carbon Footprints?

As the poultry industry moves toward becoming a more energy efficient and sustainable industry, it is important that a complete evaluation of the carbon footprint of each segment of the poultry industry is done. Reductions in the carbon footprint of the poultry production will require the identification and adoption of on-farm management practices and technological changes in production and waste management that can result in positive net changes for producers and the environment.

The results from a study at the University of Georgia evaluating the carbon footprint of poultry farms in the U.S. indicate that the use of fossil fuels, specifically propane gas, for heating houses generated the most GHG on broiler and pullet farms.

In this study about 68 percent of the emissions from the broiler and pullet farms were from propane use, while only 0.3 percent of the total emissions from breeder farms were from propane use. The propane used on these farms is mainly for heating during brooding and the colder times of the year. On breeder farms, about 85 percent of GHG emissions were the result of electricity use, while the pullet and broiler grow-out farms had 30 and 29 percent emissions, respectively, from electricity use.

Results from studies looking at energy audits from poultry farms indicate that a large amount of energy in the form of electricity is used primarily for lighting and ventilation. These results put the poultry industry in a favorable light when compared to other protein production sectors. It was recently reported in Germany that pound of chicken meat resulted in the emission of 7.05 pounds of CO2e (ThePoultrySite, 2010). The highest proportion (48.3 percent) of the emissions came from the production farms when compared to the breeder and hatchery farms.

A similar report was given on swine production, which indicates that 8.8 pounds of CO2e was emitted to produce 1 pound of pork. In this swine study, 53 percent of the emission burden was attributed from the nursery to finish stages of production as compared to the sow and gestation stages (Miller, 2007). In both of these studies, it is clear that the growing stages of production are where most of the emissions occur.

Improving Energy Efficiency

Improvements in energy use on poultry farms have to be approached on an individual farm basis. Any savings in fossil fuel use will reduce emissions and thus reduce the farm’s carbon footprint. There are a number of actions that can be taken to reduce the use of fossil fuel, specifically propane, on the poultry farms, including:

- Enclosing and insulating curtain openings in houses without solid walls to reduce heat loss and thus propane use;

- Installing attic inlets to allow the utilization of the attic area as a solar energy collector;

- Adding insulation to the walls and ceilings to reduce heat loss;

- Installing circulatory fans to reduce temperature stratification and using radiant heaters instead of gas heaters for brooding;

- Choosing efficient exhaust fans for new buildings and replacing worn out fans in older/ existing houses;

- Selecting energy-efficient generators and incinerators, which will pay for themselves quickly with the amount of energy they conserve; and

- Replacing incandescent lights with compact fluorescent lights to help reduce electricity use and costs.

Although many farms already have some of these upgrades, there are still a number of poultry houses that have a lot of room for improving the efficiency of their heating systems and electricity use. It is not uncommon to see projected reductions of 40-60 percent. Visit the UGA Poultry House Environmental Management and Energy Conservation website for more ideas on reducing energy use.

Using Alternative Energy

Currently, there are a number of alternative energy sources that could be considered for poultry production. The most common are solar, wind, and biomass. While these alternatives may eventually prove effective, they remain in the proving stage and are expensive to implement. Even though solar energy is readily available, it has a high cost of recovery when compared to fossil fuels. Wind energy is not as accessible as solar energy and is not practical in all areas. Biomass has a low power density, and while it could not practically be used to power a poultry farm, it could be used to provide heat in poultry houses.

Approximately 10.2 million tons of poultry litter is generated annually in the U.S. A large amount of this litter is applied to croplands and pastures as a means of soil amendment. Alternatively, the litter in poultry houses could be used as renewable energy source. It can be used as biomass for pyrolysis to produce liquid biofuels (which would be considered carbon-neutral) to power equipment on the farm. Replacing fossil-fuel energy with biofuel to operate equipment is considered carbon neutral because the contemporary carbon cycle produces and consumes this liquid fuel.

A coproduct from biomass pyrolysis is biochar. This can be used as a soil amendment that can sequester the carbon in soils for centuries. Biochar has the capacity to reduce CO2 emissions, thereby making the system carbon-neutral or in some instances carbon-negative.

Manure Management

Proper management of bedding and manure stores will reduce GHG emissions since substantial amounts of the methane and nitrous oxide are produced under suboptimal conditions. Several factors affect methane and nitrous oxide emissions from manure, including temperature, moisture content, and oxygen. Methane production from animal manures increases with increased temperature. This is where the majority of the methane is emitted during poultry production. The following mitigation strategies can help to reduce GHG emissions:

- Handle manure as a solid or spread it on land so it decomposes aerobically and produces little or no methane.

- Avoid prolonged litter storage, which can increase methane emissions.

- Ensure manure heaps are covered to keep them dry.

- Add high carbon substrate to manure heaps.

- Compact solid manure heaps, which tends to reduce the oxygen entering the heap and therefore maintains an anaerobic condition in the heap. However, there is a drawback in that the anaerobic condition is favorable for methane production and one GHG would be swapped for another (that is, reducing nitrous oxide but increasing methane emission).

What about Carbon Credits?

An international cooperation of 190 countries, including the U.S., formed the Kyoto protocol, which has guided the global plan to reduce GHG emissions and invest in renewable technologies in developing countries. This global, compliance-driven market was valued at $120 billion in 2009, and estimates indicate that by 2020 it could be worth over a trillion dollars.

The U.S. has a total voluntary market that has been estimated to be about $400 million in 2009 (Ecosystem Marketplace, 2010). It is voluntary in the U.S. because there are currently no limits on the amount of GHG that can be emitted. In the U.S. private trades are made between buyers and sellers. While these trades are not regulated, there are several credible registries, like California’s cap and trade system.

A “carbon credit” represents a certified reduction in GHG emissions equal to one metric tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent. These carbon credits can be generated when producers voluntarily take action to reduce emissions that would have been emitted under normal production operations. Since the costs of verifying these reductions and facilitating these trades are quite high, it is usually only feasible to obtain carbon credits when significant reductions can be made.

Summary

From all indications, the majority of GHG emissions generated from the poultry industry occur during the production stage (i.e. the grow-out, pullet, and breeder farms) and specifically come from propane and electricity use. It is therefore important that the poultry industry continues to work on improving efficiency when using fossil fuels in an effort to reduce GHG emissions. Engineering approaches will be necessary to address heating strategies and electricity use in the poultry houses. Agricultural engineers and poultry scientists are constantly working on ways to make these houses more efficient. Other ways of becoming more efficient are through improving growth rate and feed efficiency. This has already been greatly improved in the poultry industry through genetic selection and improved nutrition.

When compared to other animal production systems, the modern broiler, layer, and turkey are considered to be very efficient. However, the scale of the U.S. poultry sector is vast and even small impacts can add up; therefore, we must be vigilant and continue working to reduce emissions and make the industry more sustainable.

References

Ecosystem Marketplace. (2010). State of the voluntary carbon markets report 2012. Retrieved from http://www.ecosystemmarketplace.com/pages/dynamic/web.page.php?page_id=7737§ion=home.

Global Change Office, Office of the Chief Economist, U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2008, August) U.S. Agriculture and Forestry Greenhouse Gas Inventory: 1990-2005. (Technical Bulletin No. 1921, pp. 11-18). Retrieved from http://www.usda. gov/oce/climate_change/AFGGInventory1990_2005.htm.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2006). 2006 IPCC guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories. Retrieved from http://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/index.html.

Johnson, J.M., Franzluebbers, A.L., Weyers, S.L., & Reicosky, D.C. (2007). Agricultural opportunities to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. Environmental Pollution, 150(1) 107-124.

JRC European Commission. (2007). Carbon footprint: What it is and how to measure it.

Miller, D. (2010, March 15). Peeling away the layers of pork’s carbon footprint. National Hog Farmer. Retrieved from http://nationalhogfarmer.com/environmental-stewardship/regulations/layers-of-porks-carbon-footprint-0315.

Monteny, G.J., Groenestein, C.M., & Hilhorst, M.A. (2001). Interaction and coupling between emission of methane and nitrous oxide from animal husbandry. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems, 60(1-3), 123-132.

ThePoultrySite News Desk. (2010, March 19). Wiesenhof reports its first CO2e footprint. ThePoultrySite. Retrieved from http://www.thepoultrysite.com/poultrynews/19763/wiesenhof-reports-its-first-co2-footprint.

Office of Atmospheric Programs, U.S. EPA. (2006, April). Inventory of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and sinks: 1990-2004. (USEPA #430-R-06-002). Retrieved from http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/Downloads/ghgemissions/06_Complete_ Report.pdf.

Office of Atmospheric Programs, U.S. EPA. (2007, April). Inventory of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and sinks: 1990-2005. (EPA 430-R-07-002). Retrieved from http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/Downloads/ghgemissions/07CR.pdf.

Office of Atmospheric Programs, U.S. EPA. (2013, April). Inventory of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and sinks: 1990-2011. (EPA 430-R-13-001). Retrieved from http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/Downloads/ghgemissions/US-GHG-Inventory-2013-Main-Text.pdf.