y Douglas L. Fulnechek, DVM

Senior Public Health Veterinarian, Zoetis

Since public interest drives public policy, it’s no surprise USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) tightened the standards for the maximum acceptable limit of Salmonella at processing.

The poultry industry is making progress. The Salmonella prevalence in chicken parts is dropping, based on USDA data.1 However, we have a long way to go — and the pressure is on.

Salmonella’s origin

Salmonella doesn’t originate at the processing plant. It comes from live production. That’s why further reducing its prevalence will require intervention throughout the entire poultry production chain.

Unfortunately, this is easier said than done because young chicks are easily colonized, especially during the first 2 weeks of life. Their normal intestinal flora isn’t fully developed and their immune system is naïve, which makes them a receptive host for Salmonella.

In addition, our production system practices can favor higher Salmonella exposure levels every step of the way if we don’t manage them carefully. Just one example is reusing litter, which contains Salmonella, although adequate top dressing with clean, fresh shavings can reduce early exposure.

Start with breeders

There are a lot of other ways broilers can become contaminated, and it starts with actively shedding breeders. Hens with Salmonella-infected ovaries and oviducts can vertically transmit the infection to broilers. Broilers can become infected if egg shells are contaminated with feces, which is more likely to occur if nest boxes are wet and dirty, if eggs are on the floor where Salmonella is present or if eggs sweat. Other sources are a Salmonella-contaminated egg room or contaminated transport equipment.

The most obvious way to eliminate Salmonella in hens is to eliminate flocks positive for the pathogen. While we all know this isn’t a realistic option, achieving significant reductions in shedding is a realistic goal.

One effective approach is vaccination. Researchers from the University of Georgia found that broilers had a lower Salmonella prevalence upon placement at contract farms and at processing if they were from hens vaccinated against the pathogen compared to broilers from breeders that weren’t vaccinated.2

I recommend giving pullets a couple of live Salmonella Typhimurium vaccines early — preferably on day of hatch and then a field booster — followed by an inactivated Salmonella Enteritidis vaccine at 10 weeks and then one multivalent Salmonella vaccine at about 20 weeks. Including serotypes from Groups B, C and D should help cover the majority of poultry serotypes of concern.

At the breeder farm, soiled and dirty eggs should be culled and discarded because the results with them are poor and can compromise production. If eggs are visibly clean, as they should be, and good culling practices are in place, no disinfection is needed. Egg storage is typically at 65° F to 68° F (18° C to 20° C) and should not exceed 10 to 12 days.

I am aware of some producers using disinfectant wipes on dirty eggs. This practice can increase the incidence of rotten eggs forming during incubation and increase microbial contamination of adjacent hatching chicks. It masks “problem eggs” from hatchery management, gives a false sense of security to the farmer producing them and encourages the egg producer to put more poor-quality eggs into the setting egg pack.

Cleaning is not sanitation

Standards and good handling practices for hatching eggs from farm to hatchery should be enforced. These include routine environmental sanitation of storage facilities, air handling units, egg flats and transport vehicles.

Thorough cleaning and sanitation of the hatchery overall is imperative. Let’s remember, however, that cleaning is not sanitation. The hatchery needs to be microbiologically acceptable. This can be achieved with the use of disinfectant foggers or a micro-aerosol spray routinely applied at various intervals throughout the hatchery and includes setters and hatchers. The disinfectant should be applied as part of a program designed specifically for the facility, typically working under the guidance of sanitation experts.

The ventilation system is important at all stages of production, but at the hatchery, it’s critical. It needs to be clean. Care must be taken to ensure air handling units do not pull in Salmonella-contaminated air.

All hatcheries should have a sanitation standard operating procedure in place for setters, hatchers and transfer equipment. Sanitation effectiveness should be monitored by both ATP-linked bioluminescence and bacterial culture and identification. ATP stands for adenosine triphosphate, an organic chemical that’s used as a marker for contamination. Combined with luminescence technology, it can detect nonspecific contamination immediately.3

ATP-linked bioluminescence is easy and quick, but it may not be appropriate for vaccine-equipment systems. Bacterial culture and identification will identify specific organisms remaining on contact surfaces.

Preventing Salmonella in broilers

At hatch, competitive-exclusion cocktails administered by spray or gel for improved gut health can help reduce Salmonella colonization to some degree. However, recent broiler-pen studies affirm that live Salmonella vaccination has an even greater impact.4,5

Although most producers are already vaccinating breeders against Salmonella, vaccination of broilers against the pathogen is just catching on. This prompted us to test broiler rinses at rehang for Salmonella in flocks that received Poulvacâ ST at hatch followed by a field boost. This is a modified-live vaccine labeled for the reduction of Salmonella Enteritidis, Salmonella Heidelberg and Salmonella Typhimurium colonization.

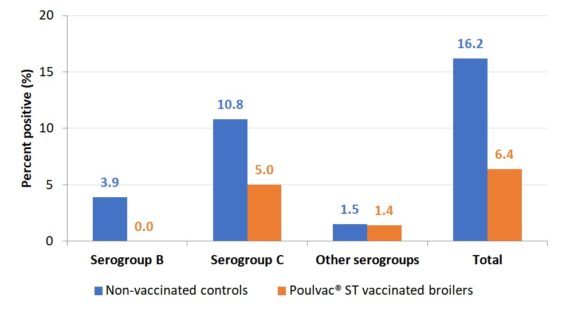

In one trial involving over 9.5 million conventionally raised broilers (4 million vaccinates), there was a 60% reduction in carcasses positive for Salmonella compared to unvaccinated flocks (Figure 1).6,7

Figure 1. Salmonella-positive rinses at rehang in conventional broilers vaccinated against Salmonella with a modified-live vaccine compared to unvaccinated controls

Click chart to enlarge

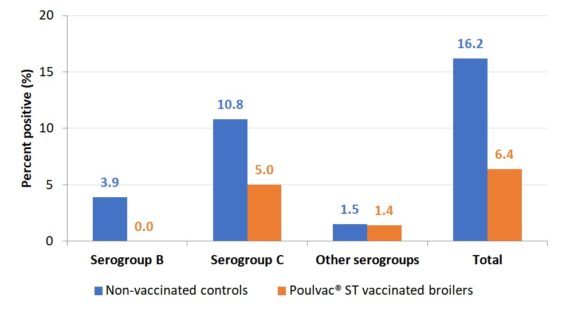

In another trial involving 8.5 million broilers raised without antibiotics (4 million vaccinates), there was about a 30% reduction in positive carcasses and 40% reduction in parts positive for Salmonella (Figure 2).8,9

Figure 2. Salmonella-positive rinses at rehang and parts in broilers vaccinated against Salmonella with a modified-live vaccine and raised without antibiotics as compared to unvaccinated controls

Click chart to enlarge

Besides vaccination, proper ventilation and litter management to reduce litter moisture will help keep Salmonella numbers down during growout. So can drinking water acidification, which can reduce Salmonella levels in the crop. For at least the last 72 hours, water should be progressively acidified to the lowest pH that doesn’t affect water consumption.

Since broilers with a healthy intestinal tract are likely to carry less Salmonella,10 coccidiosis control is important. Composting or windrowing litter and avoidance of overcrowding are likewise useful. So is flock downtime — 18 days is acceptable, but if the contract allows, 21 days is better.

Feed withdrawal before processing needs to be just right. The goal is to reduce intestinal contents, but if birds get so hungry they start eating litter, they’re more likely to have Salmonella in their crops. The target withdrawal time is 8 hours. Intestinal strength diminishes with withdrawals of more than 10 hours.

Salmonella in feed

Speaking of feed, it’s best to consider all feed ingredients as Salmonella-contaminated, and even if they aren’t, they need to be protected from contamination. One important way to do that is by controlling dust when raw ingredients are delivered since dust can be a major source of Salmonella.

When heating feed for pelleting, the temperature needs to reach 185° F (85 °C). Be sure to avoid condensation in the pellet cooler. Formaldehyde and propionic acid can also be used to eliminate Salmonella in feed.

Feed mill equipment must be sanitized after cleaning. It’s imperative to have a robust pest-control program and tight biosecurity throughout the mill. Work shoes in particular can transfer Salmonella. Wild birds and, for that matter, all other animals need to be kept away from the mill and flocks.

Last chance: processing

As we all know, processing is our last chance to contain or eliminate Salmonella on chicken carcasses.

There should be a pre-scald carcass brush wash. It also helps to use acidic sanitizers on picker rails.

Scalders can be an intervention. If you use an acid sanitizer, you can decrease the scalder temperature to help maintain skin integrity, which reduces bacterial attachment and improves picking. The scalder temperature, however, shouldn’t go below 123° F (50.5° C), in which case Salmonella will grow. In addition, if you reduce fat liquefaction, and fat on equipment and in the chiller, you not only improve yield, you’ll have less Salmonella.

The evisceration process must ensure sanitary dressing. This might require reducing the line speed, adjusting equipment or making staff changes to prevent digestive-tract spillage and get the job properly done.

Producers have several options for chilling, including peroxyacetic acid (commonly called PAA), hypochlorus acid, which is chlorine, and buffered sulfuric acid. Organic and inorganic acids are also possibilities.

Post-chill, antimicrobial and/or acidified immersion baths should be used. Processing belts should be treated continuously with an antimicrobial such as chlorine, a stabilized acid or peroxyacetic acid.

When proper processing procedures are coupled with live-side efforts, they can go a long way toward reducing the prevalence of Salmonella on chicken carcasses.

Communication is essential

Based on my 29 years as a supervisory public health veterinarian, I can tell you that communication among everyone involved in poultry production is essential for good Salmonella control. Anecdotally, I can report that poultry companies with good management and communication among all facets of production have better results.

I recommend that live production managers attend FSIS meetings at least once monthly and review condemned carcasses along with processing plant management. Live production managers as well as service technicians and processing plant managers should collaborate on feed withdrawal to find what works best to prevent litter picking yet reduce intestinal contents.

There’s no doubt that a properly executed Salmonella prevention and control plan requires a lot of hard work and resources, but it’s not optional. It’s the cost of doing business. It prevents recalls, protects a producer’s brand and, in doing so, can save a lot of heartache and money.

Editor’s note: The opinions and recommendations presented in this article belong to the author and are not necessarily shared by the editors of Poultry Health Today or Zoetis.

1 Peterson A. The Chicken Parts Performance Standard: Opportunities Ahead. Kemin.com.

2 Dorea F, et al. Effect of Salmonella Vaccination of Breeder Chickens on Contamination of Broiler Chicken Carcasses in Integrated Poultry Operations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010 Dec;76(23):7820-7825.

3 Chollet R, et al. Use of ATP Bioluminescence for Rapid Detection and Enumeration of Contaminants: The Milliflex Rapid Microbiology Detection and Enumeration System.

4 Data on file, Study Report No. 04-16-7ADMJ, Zoetis, LLC.

5 Data on file, Study Report No. 04-17-7ADMJ, Zoetis, LLC.

6 Data on file, Study Report No. 04-16-7ADMJ, Zoetis, LLC.

7 On file, Integrated Food Safety Management From Zoetis. Poulvacâ ST: Protecting Profitability From the Inside Out. Integrated Food Safety Management From Zoetis.

8 Data on file, Study Report No. 01-17-7ADMJ, Zoetis, LLC.

9 On file, Integrated Food Safety Management From Zoetis. Poulvacâ ST: Protecting Profitability From the Inside Out. Integrated Food Safety Management From Zoetis.

10 Da Costa M, et al. Studies on the interaction of necrotic enteritis severity and Salmonella prevalence in broiler chickens. Proceedings of the Sixty-Seventh Western Disease Poultry Conference. 2018;55-56.

Keys to successful coccidiosis control with a bioshuttle program, By Greg Mathis, PhD, Southern Poultry Research

Source: Poultryhealthtoday.com

Resistance is unlikely to be a problem in coccidiosis bioshuttle programs, Greg Mathis, PhD, Southern Poultry Research, told Poultry Health Today.

Bioshuttle programs start with hatchery vaccination against coccidiosis followed by use of an in-feed anticoccidial. Alternative products are also often used, Mathis said.

The key to success with bioshuttle programs in no-antibiotics-ever (NAE) production, he said, is allowing immunity to develop after vaccination. Toward that end, Mathis recommended one and a half or two coccidia cycles after vaccination — the coccidial lifecycle being 7 days — before using an in-feed anticoccidial.

He cautioned that when an anticoccidial is administered after vaccination, it must not be done too soon because it could kill off vaccinal coccidial oocysts before some immunity has developed. The appropriate time to administer an in-feed anticoccidial is about 14 to 16 days after vaccination, he said.

Sensitive oocysts

Although coccidial resistance remains a major concern, it’s unlikely to develop in a bioshuttle program because every time the vaccine is used, coccidia that are still sensitive to in-feed anticoccidials are reintroduced to the poultry house, Mathis said.

Ionophores can’t be used in NAE production systems because they are considered antibiotics by the Food and Drug Administration, but in conventional production, they are viewed as a valuable tool.

The return of zoalene

Mathis pointed out there are only seven non-ionophore anticoccidials available in the US and all have been around for decades.

One of them is zoalene, which returned to the U.S. poultry market in 2014 following a 9-year hiatus stemming from an ingredient shortage.

The product’s return has been helpful to the industry, particularly to NAE production systems that often use it in a bioshuttle program with vaccines, Mathis said. Because there is some coccidial leakage with zoalene, it allows some immunity to develop.

Alternative products in the rotation

Antibiotic alternatives are being used more frequently as part of a bioshuttle program, but they are not used as stand-alone products; they tend to be used continuously through production to help prevent coccidiosis and necrotic enteritis, he said.

Producers understand how probiotics work and therefore use them widely in coccidiosis-control programs. Other alternatives used include saponins such as triterpenoids and yucca extracts, as well as essential oils, which have antibacterial and antiprotozoal activity, Mathis said.

Among the feed acidifiers, butyric acid improves villi growth and strength and has generated a lot of interest among producers. Any feed acidification will reduce Clostridium and Salmonella as well, he added.