The poultry industry’s approach to highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) should be informed by the behaviors and characteristics of wild bird species, according to Dr. Carol Cardona, a professor at the University of Minnesota’s Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences.

During the Council for Agricultural Science and Technology’s (CAST) webinar titled “HPAI and Its Impact on Food Production Industries,” Dr. Cardona highlighted the significance of migration in understanding influenza ecology.

“Migration is a key behavior influencing influenza dynamics in birds,” Dr. Cardona said. She elaborated that bird groups form, disperse, and reform during migration. Birds gather for breeding, and if one bird is infected, many others can contract the virus by the end of the breeding season.

“These groups then carry their influenza strains to new environments, facilitating the mixing and spreading of viruses,” she explained.

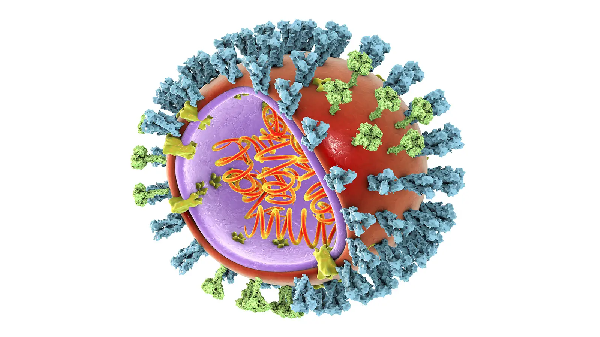

New viruses can emerge when a bird is infected with more than one type of virus. In reservoir hosts, which carry the pathogen without illness, multiple viral subtypes can combine, often leading to new influenza strains that may not be stable.

Species and Habitats

Dr. Cardona pointed out that various species of birds and mammals capable of carrying influenza A viruses do not migrate and remain stationary.

“This results in a genetic exchange between resident animals as populations move seasonally,” she stated.

Aquatic habitats, in particular, are conducive to hosting a variety of influenza viruses. Mallards, which live in water-rich environments, are likely to have a wider array of avian influenza viruses compared to wood ducks that nest in trees.

The severity of the virus varies by species, affecting how birds respond to infection. For example, a mallard may show minimal or no symptoms when infected with a virus that could be fatal to white leghorn chickens.

“Rather than viewing birds as a single entity, we should recognize their diversity. Their collective biology shapes the future ecology of influenza viruses,” Dr. Cardona concluded.